What Is a Phishing Attack?

A phishing attack is a type of cybercrime where malicious actors send fraudulent communications, often disguised as legitimate messages, to trick individuals into revealing sensitive information or taking actions that compromise their security.

These attacks typically involve emails, text messages, or fake websites, and rely on social engineering tactics to manipulate victims into clicking malicious links, downloading malware, or providing personal details like passwords, bank account information, or credit card numbers.

Phishing messages often contain official logos, brand names, or spoofed sender addresses, creating a convincing facade. Victims who respond to such messages or click on malicious links may inadvertently grant attackers access to their accounts or install malware on their devices, escalating the scope of the attack and potential damage.

This is part of a series of articles about website security

In this article:

- How Does Phishing Work?

- How Is Phishing Evolving in the Age of Deepfakes and GenAI?

- Common Types and Examples of Phishing Attacks

- How to Detect a Phishing Attempt

- Anti-Phishing Technologies

- Best Practices to Prevent Phishing

How Does Phishing Work?

Phishing works by following a sequence of steps to deceive and extract sensitive data from the target.

- First, the attacker gathers information about the victim or organization, such as email addresses, common contacts, or business operations. This reconnaissance helps craft a convincing and relevant message.

- Next, the attacker creates a fraudulent communication channel, often by registering a domain that looks similar to a legitimate one or spoofing an existing email address. The message is then composed to trigger an emotional or urgent response—such as a warning about account compromise, a fake invoice, or a request for immediate action.

- When the victim clicks a link or opens an attachment, they are usually directed to a counterfeit website that mimics the real one. Here, they are prompted to enter login credentials, payment details, or other sensitive information. In some cases, the link or file delivers malware, enabling further compromise of the victim’s device or network.

- Finally, the stolen data is transmitted to the attacker, who may use it for identity theft, financial fraud, or unauthorized access to corporate systems. This entire process relies heavily on exploiting trust and bypassing technical defenses by targeting human behavior.

Related content: Read our guide to man in the middle attack

How Is Phishing Evolving in the Age of Deepfakes and GenAI?

As generative AI (GenAI) and deepfake technologies mature, phishing attacks are becoming more persuasive and harder to detect. Attackers can now generate audio deepfakes that convincingly mimic the voices of executives or colleagues, tricking employees into authorizing wire transfers or disclosing sensitive information during live phone calls. In email and chat-based phishing, GenAI tools are used to craft flawless, context-aware messages in any language, eliminating many of the grammar and spelling errors that traditionally signaled fraud.

Additionally, GenAI enables attackers to automatically tailor phishing content using public data scraped from social media, press releases, or corporate websites. This level of personalization makes messages seem more authentic and relevant to the recipient, increasing the likelihood of success. As AI models continue to evolve, they may be used to dynamically adjust phishing campaigns in real time based on user behavior, making detection and prevention significantly more difficult.

Common Types and Examples of Phishing Attacks

Here are the common types of phishing attacks. with examples sourced from Terra Nova Security, USecure, and KeepNet Labs.

1. Bulk Email Phishing

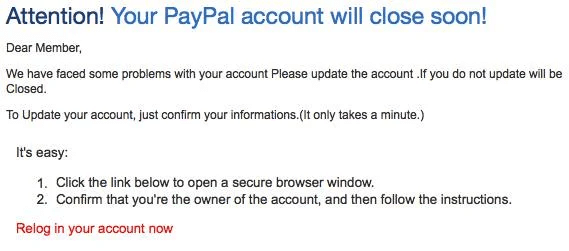

Bulk email phishing, also known as “spray-and-pray” phishing, involves sending large volumes of generic fraudulent emails to as many recipients as possible. The messages usually contain urgent requests like “verify your account” or “reset your password,” with links directing users to fake websites.

This approach relies on volume—although many recipients ignore the messages, even a low response rate translates to significant success for attackers. Bulk phishing kits are widely available on the dark web, enabling low-skill attackers to launch campaigns.

Example:

An attacker sends a fake PayPal alert stating the victim’s account will be deactivated unless they confirm credit card details. The email links to a spoofed PayPal login page used to harvest credentials.

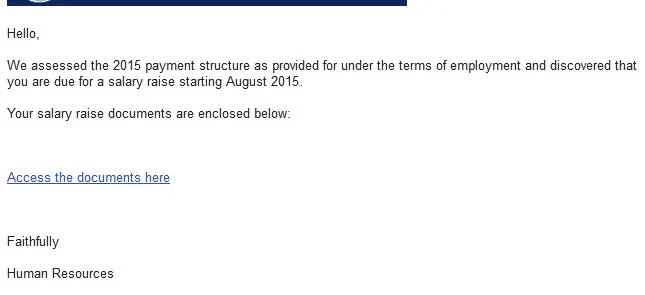

2. Spear Phishing and Whaling

Spear phishing targets specific individuals or organizations, with attackers researching their victims beforehand to craft convincing, relevant, and often personalized messages. These emails may reference recent projects, use the names of colleagues, or appear to originate from trusted contacts or leadership.

Such personalization increases the likelihood that recipients will engage with the message, making spear phishing one of the most dangerous forms of phishing. Attackers may use compromised business accounts or exploit social media profiles to enhance credibility.

Whaling is a specialized spear phishing attack focused on high-profile targets such as executives, board members, or senior managers. Attackers design emails to imitate critical business communications—such as legal notices, requests from regulators, or urgent wire transfer approvals—that demand immediate attention from leaders.

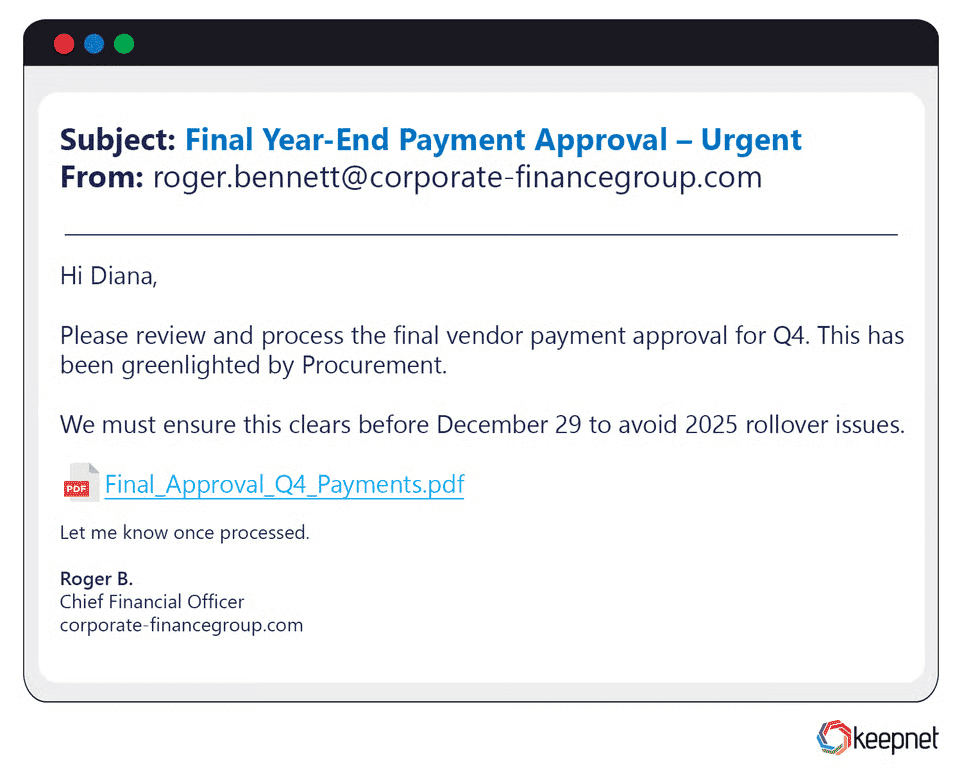

Example:

A CFO receives an email seemingly from the CEO referencing an actual upcoming merger. The message urgently requests financial documents, leading to a data breach when the CFO complies.

3. Business Email Compromise (BEC)

Business email compromise (BEC) targets organizations by impersonating executives, business partners, or vendors to request payments or sensitive data. Unlike other phishing types, BEC usually does not contain attachments or links. Instead, the attacker seeks to establish ongoing correspondence to manipulate employees into authorizing financial transactions or sharing proprietary information.

BEC attacks typically require prior research and may involve compromising legitimate business accounts through credential theft. Hackers use pressure tactics or fake urgency to force employees into bypassing standard verification procedures.

Example:

An employee receives an email from a spoofed address impersonating the company CEO, requesting a confidential wire transfer to a new supplier. Believing the message is real, the employee initiates the transfer.

4. AI Phishing

AI phishing uses artificial intelligence to automate and personalize phishing campaigns at scale. Attackers use generative AI models to craft highly convincing messages, replicating writing styles or even mimicking specific individuals.

After the initial attacks, AI-driven chatbots or conversational agents can engage targets at scale and in a human-like manner, increasing the likelihood of successful deception. These campaigns enable hyper-personalized attacks that are much harder for recipients to detect as fraudulent.

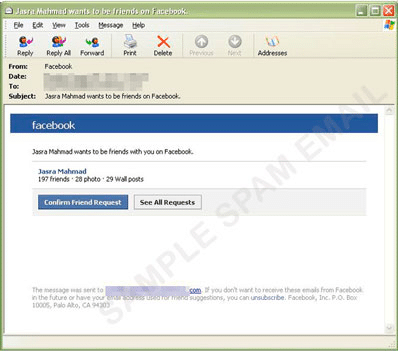

5. Social Media Phishing

Social media phishing targets users on platforms like Facebook, LinkedIn, or Twitter. Attackers create fake accounts or hijack compromised profiles to send malicious messages, share phishing links, or trick users into revealing credentials through direct messages or posts.

Since trust is often higher on social networks, attackers exploit relationships and social circles to propagate scams more effectively. By compromising or cloning social accounts, they might pose as friends or colleagues, reference recent online activity, or pretend to represent popular brands and events.

Example:

A Facebook user receives a friend request from a profile with several mutual connections. After accepting, the “friend” sends a message with a link to a video that installs malware once clicked.

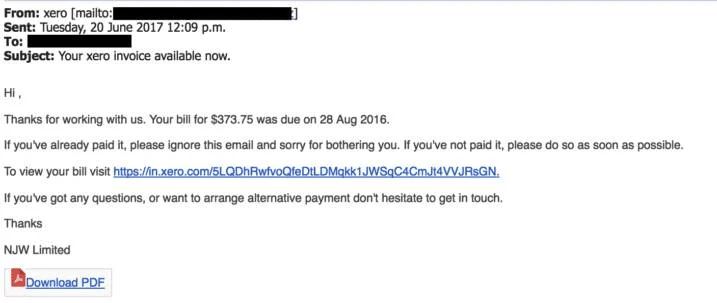

6. Clone Phishing

Clone phishing involves duplicating a legitimate email previously received by the victim but replacing original links or attachments with malicious alternatives. The attacker may spoof the sender’s address to make the message appear as an official resend or update.

Because recipients often recognize the format and context of the original email, they are more likely to trust clone phishing attempts.

Example:

A user receives what appears to be a follow-up email from IT support with a revised “HR policy document.” The attached file contains macros that deploy spyware when opened.

7. Vishing (Voice Phishing)

Vishing uses phone calls or voice messages to deceive victims. Attackers may impersonate bank officials, tech support agents, or government representatives, using social engineering to trick individuals into divulging credentials, account numbers, or one-time authentication codes.

Automated calling systems allow attackers to reach thousands of targets with recorded messages. Some vishing campaigns combine email or SMS phishing to strengthen their narrative. Recent techniques exploit caller ID spoofing to appear as calls from trusted institutions.

8. Smishing (SMS Phishing)

Smishing attacks use SMS or text messages as the delivery channel. Attackers send fraudulent texts claiming to be from banks, delivery services, or government agencies, often containing links to malicious websites or instructions to reply with confidential information.

Because people tend to trust text messages and act quickly on them, smishing is an effective way for attackers to reach mobile users. The messages may urge recipients to act immediately, such as validating an account or avoiding service interruption.

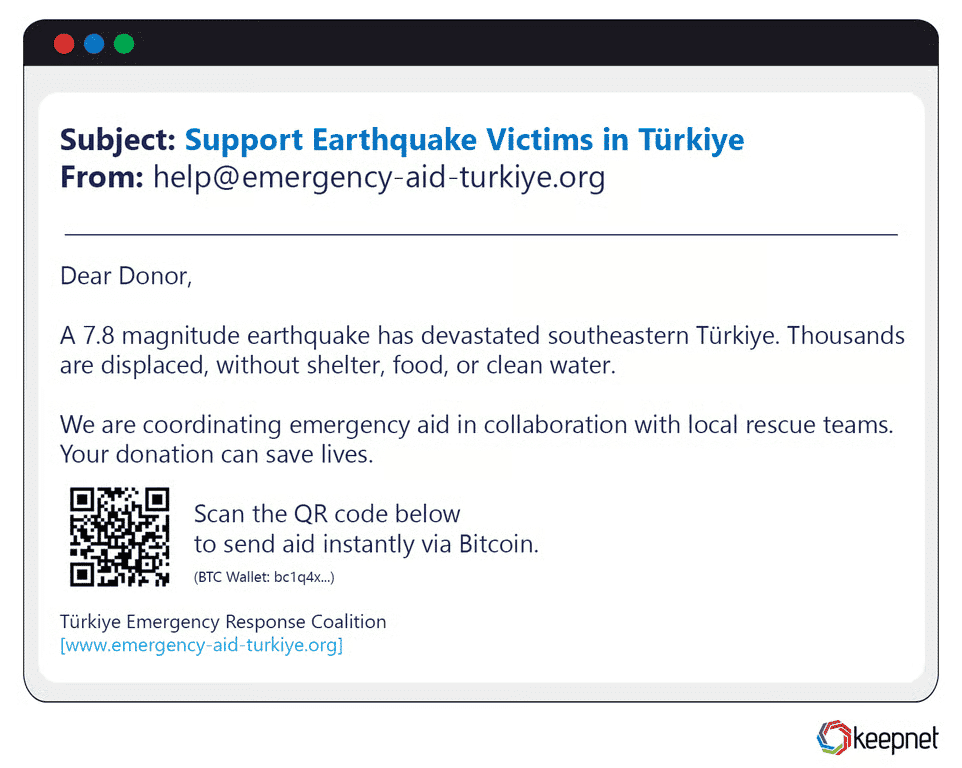

9. Quishing (QR Code Phishing)

Quishing employs malicious QR codes that, when scanned with a smartphone, redirect users to phishing websites or trigger malware downloads. Attackers circulate QR codes through emails, printed materials, posters, or social media posts.

Users associate QR codes with convenience, rarely scrutinizing the destination URL before being redirected. Attackers capitalize on this trust, embedding malicious links or prompts for credential input.

Example:

A poster at a public venue offers a “free coffee voucher” via QR code. Scanning it opens a spoofed site asking for login details tied to the victim’s digital wallet app.

10. Man-in-the-Middle Phishing

Man-in-the-middle (MITM) phishing involves intercepting communications between two parties, usually via compromised Wi-Fi networks, malicious browser extensions, or fake websites. Attackers capture, manipulate, or relay messages, recording sensitive data such as login details or financial transactions.

Often, victims believe they are communicating directly with a trusted party, unaware that an attacker is monitoring or altering the session in real-time. MITM phishing scenarios can lead to undetected credential theft or unauthorized fund transfers.

Example:

A victim connects to a spoofed public Wi-Fi hotspot labeled “Free Airport Wi-Fi.” The attacker intercepts traffic and captures credentials entered on login pages for email and banking services.

The examples in this section were sourced from Terra Nova Security, USecure, and KeepNet Labs.

How to Detect a Phishing Attempt

There are several ways to identify indicators of phishing attacks.

1. Content and Language Red Flags

Phishing messages often deviate from the professional tone, grammar, and formatting used by legitimate organizations. This can include incorrect salutations, missing branding elements, or inconsistent date/time formats. Attackers frequently use emotional triggers like urgency (“You must act now”), fear (“Your account has been locked”), or reward (“You have won a prize”) to override rational decision-making.

Additionally, legitimate companies rarely request sensitive information such as passwords or credit card details via email. Spotting unfamiliar file types in attachments or hyperlinks embedded in images can also be an indicator of malicious intent.

Important note: The use of generative AI has significantly improved the quality of phishing messages, making them much more difficult to detect, even by aware and vigilant users. This makes it critical to put in place additional defensive measures.

2. Email Header and Domain Analysis

A detailed review of the email header can uncover signs of spoofing or domain impersonation. The “From” field shown in the email client is often forged, so it’s essential to check the actual “Return-Path,” “Received,” and “Reply-To” fields in the header. In legitimate emails, these typically align with the organization’s official domain.

Phishing emails may contain subtle typos (e.g., micros0ft.com instead of microsoft.com) or domains registered recently and unrelated to the sender. Automated analysis can involve checking the sending IP address against DNS records, SPF (Sender Policy Framework), DKIM (DomainKeys Identified Mail), and DMARC (Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting, and Conformance) results to verify authenticity.

3. Suspicious Link Inspection

Attackers often disguise malicious links behind seemingly harmless text or buttons. Hovering the mouse over a link without clicking reveals the actual destination URL, which can then be examined for anomalies.

Look for unusual subdomain chains (e.g., login.bank.example.com.attacker-site.com), extra punctuation, homoglyph substitutions (characters that look similar, such as “l” and “1”), or the use of HTTPS certificates from unknown or free issuers. Shortened URLs should be expanded using trusted tools before visiting.

For enterprise security, sandboxing the link in a secure analysis environment allows examination of the destination site’s content, scripts, and network behavior without risk to the user.

4. Anomalous Sender Behavior

A phishing attempt may come from an address that appears valid but exhibits behavior inconsistent with the sender’s normal patterns. Examples include sending messages outside usual business hours, introducing unexpected urgency in routine matters, or requesting information they typically would not need. Compromised accounts often reuse previous conversation threads to appear credible but insert malicious links or new payment instructions.

Monitoring sender frequency, geographical login origins, and sudden shifts in communication style can help flag potential threats. Any financial or sensitive data request, especially involving changes to payment processes, should be verified through an independent channel such as a phone call to a known contact number.

Anti-Phishing Technologies

Here are some of the main technologies used to thwart phishing attacks.

Browser-Based Phishing Detection

Consumer browsers such as Chrome, Firefox, and Edge maintain constantly updated lists of known phishing and malware-hosting domains, blocking access when a match is found. Modern browsers also use SSL/TLS certificate validation to flag expired, self-signed, or mismatched certificates that might indicate a fake website.

Beyond these basic measures, enterprise browser security platforms implement heuristics to detect suspicious page elements, such as login forms on non-secure pages or domain name obfuscation using Unicode characters. They often provide managed browser extensions or endpoint protection plugins that add custom phishing blocklists, enforce HTTPS-only browsing, and analyze web page scripts for malicious behavior before allowing user interaction.

Email Filtering and Secure Email Gateways

Email filtering systems and secure email gateways (SEGs) serve as the first line of defense against phishing. They inspect inbound and outbound messages using a combination of static rules, heuristics, and machine learning algorithms trained on large datasets of known phishing attempts.

Key checks include analyzing the sender’s domain reputation, validating SPF, DKIM, and DMARC records, scanning embedded URLs against threat intelligence databases, and detecting suspicious attachment types such as executable files or password-protected archives.

Advanced SEGs also perform real-time URL rewriting and follow the link at click-time to detect redirects or payload changes. Some integrate with data loss prevention (DLP) tools to stop outbound transmission of sensitive information.

Multi-Factor Authentication

Multi-factor authentication (MFA) ensures that a stolen password alone cannot grant access to an account. Common second factors include time-based one-time passwords (TOTPs) generated by authenticator apps, hardware security keys (such as YubiKey or FIDO2 devices), and biometric identifiers like fingerprints or facial recognition.

While SMS-based codes are widely used, they are more vulnerable to SIM-swapping attacks, so security teams increasingly prefer phishing-resistant MFA methods like cryptographic keys that validate the origin of the login request.

MFA can be enforced across VPN access, SaaS platforms, and internal systems, and when integrated with adaptive risk-based authentication, it can prompt additional verification for logins from new devices, unusual geolocations, or abnormal usage patterns.

Real-Time Threat Intelligence Feeds

Real-time threat intelligence feeds aggregate and distribute live data about phishing campaigns, malicious domains, compromised IPs, and other indicators of compromise (IOCs). They pull from diverse sources—such as security vendor telemetry, global honeypots, incident reports, and open-source intelligence (OSINT)—to keep detection systems updated within minutes of a threat emerging.

When integrated into email security gateways, firewalls, and SIEM platforms, these feeds enable automated blocking of malicious infrastructure and allow security analysts to prioritize alerts based on active threat data. Some feeds specialize in phishing-specific intelligence, including domain generation algorithm (DGA) patterns, newly registered domains mimicking brand names, and credential-harvesting landing pages.

Automated Takedown Services

Automated takedown services continuously scan the internet for domains, websites, and accounts impersonating an organization’s brand or employees. They use image recognition to spot logo misuse, text analysis to detect brand mentions in fraudulent contexts, and DNS monitoring to identify suspicious lookalike registrations.

Once identified, the service contacts registrars, hosting providers, or platform operators to initiate takedown procedures. Some services leverage pre-established legal agreements to accelerate removal, while others deploy countermeasures such as injecting “sinkholes” to disrupt malicious site operations. Takedowns not only protect customers from ongoing scams but also limit the reuse of attacker infrastructure.

Related content: Read our guide to credential stuffing

Best Practices to Prevent Phishing

Organizations can better protect themselves against phishing attacks by implementing these best practices.

1. Conduct Regular Security Awareness Training

Training should go beyond generic warnings and instead provide employees with practical detection skills—such as analyzing email headers, recognizing homograph attacks (lookalike domains), and spotting mismatched sender names and email addresses. Sessions should include demonstrations of different phishing variants—bulk, spear, smishing, vishing—and how each might appear in the organization’s daily workflow.

Incorporating recent real-world breaches as case studies helps staff understand the real impact of phishing on finances and reputation. To keep engagement high, training can use interactive formats like quizzes, role-play scenarios, and live demonstrations of safe link inspection. Importantly, awareness training should be continuous, with short refreshers or micro-learning modules every few months, and immediate retraining for those who fail phishing simulations.

2. Keep Software and Browsers Updated

Many phishing campaigns deliver malware that exploits known vulnerabilities in outdated software. Keeping systems patched is a direct way to close these security gaps. Critical updates should be applied as soon as they are released, ideally through automated update mechanisms or centralized patch management platforms like Microsoft WSUS, Intune, or third-party enterprise tools.

Updates must cover operating systems, browsers, browser extensions, PDF readers, email clients, and other commonly exploited applications. Organizations should maintain an inventory of approved software versions and enforce compliance through endpoint management policies.

3. Implement Just-in-Time Access Controls

Just-in-time (JIT) access restricts elevated permissions so that users only have administrative or high-privilege access for a limited time and only when necessary. By reducing the constant availability of sensitive access rights, phishing attacks that successfully capture credentials have less potential for damage.

For example, if an attacker gains a compromised account’s login details, they cannot perform high-impact actions unless the user is actively granted temporary elevated rights for a specific task. JIT access can be automated through identity and access management (IAM) platforms, integrating with approval workflows and logging all privileged activity for audit purposes.

4. Regular Phishing Simulations

Phishing simulations allow organizations to measure real-world readiness against evolving threats. These exercises should be tailored to the organization’s risk profile—for example, finance teams may be targeted with fake invoice requests, while executives may see simulated whaling attempts.

Metrics such as click-through rates, credential submission attempts, and reporting rates help security teams identify weaknesses and track improvement over time. Feedback should be immediate, explaining why the simulated email was suspicious and how it could be detected in the future.

Over time, scenarios should increase in complexity, incorporating multi-channel attacks that combine email, SMS, and phone calls to simulate advanced persistent threats (APTs).

5. Use Secure Enterprise Browser Platforms

Secure enterprise browser platforms provide additional protection against phishing by combining controlled browsing environments with centralized policy enforcement. They can enforce rules that prevent users from entering corporate credentials into unapproved domains, block downloads from unknown sources, and require that high-risk websites be opened in isolated or virtualized tabs.

Some enterprise browser platforms include real-time phishing detection powered by threat intelligence feeds, automatically warning or blocking users when a suspicious page is detected. They may also log all browsing activity for audit and investigation purposes, giving security teams visibility into potential exposure points.

Integration with single sign-on (SSO) and identity access management (IAM) systems ensures that even if phishing pages are reached, credential entry is restricted to trusted login portals.

Phishing Protection with Seraphic Security

Seraphic provides comprehensive phishing protection through its Secure Enterprise Browser (SEB) platform, designed specifically to defend against the evolving landscape of web-based threats. The platform combines real-time threat intelligence with behavioral analysis to identify and block phishing attempts before they can compromise user credentials or corporate data. By implementing browser-level controls, Seraphic’s SEB creates a secure browsing environment that automatically detects suspicious domains, validates SSL certificates, and prevents users from entering sensitive information on fraudulent websites.

This proactive approach ensures that even sophisticated phishing campaigns using AI-generated content or deepfake technologies are neutralized at the point of interaction.

The platform’s multi-layered defense strategy includes automated URL analysis, content inspection, and integration with enterprise identity management systems to provide seamless protection without disrupting user productivity.

Seraphic’s solution offers centralized policy management, allowing security teams to configure custom rules for different user groups and maintain visibility into potential threats through comprehensive logging and reporting. With support for zero-trust architecture principles, the platform ensures that phishing protection scales across distributed workforces while maintaining consistent security standards.